Lessons Learned from South Africa about Multi-Ethnicity in Churches

September 25, 2015

September 25, 2015

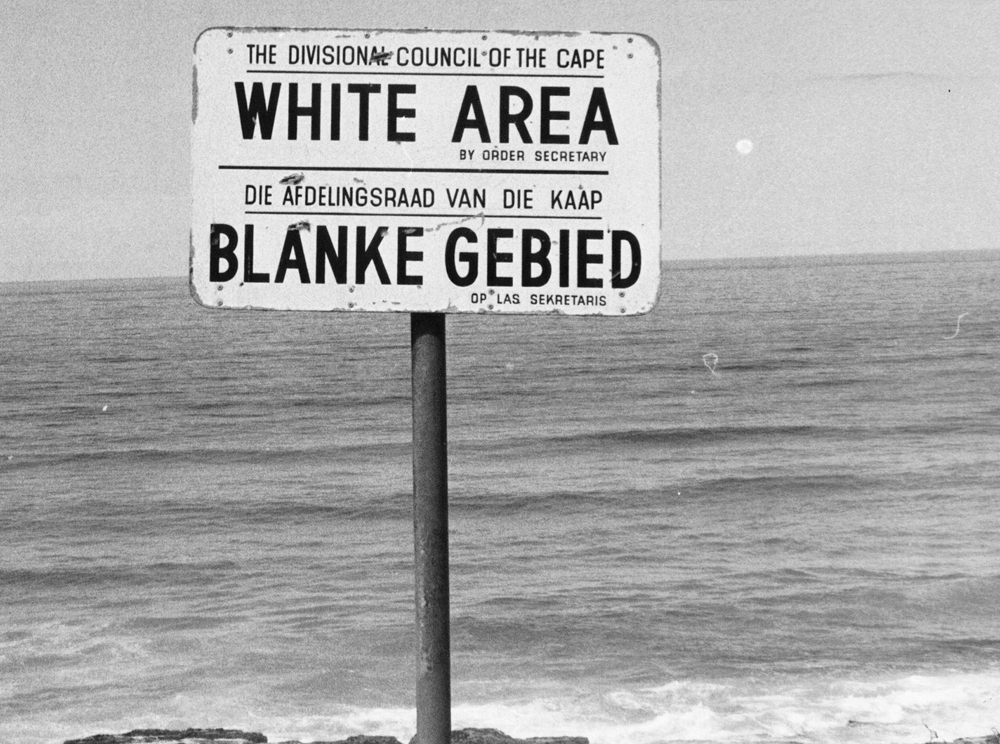

I grew up as a “coloured”1 boy in South Africa during the latter days of Apartheid. Born after the 1976 Soweto Uprising, I was spared much of the horrors of life in South Africa under white Afrikaaner rule. I did however experience the hatred of white racists, and I recall those beaches and public areas that were for “whites only.” But I also remember watching the dismantling of Apartheid, the dissolution of its systematic oppression of non-white people. I remember clearly when the Group Areas Act was repealed in 1991 because my parents bought a home in a previously ‘white neighbourhood’ while I was still a young boy.

Currently, I live in Johannesburg, South Africa, where I pastor a local church in what was previously a white part of the city. Like most pastors in South Africa, I have been forced to think about what it really means to have a multi-ethnic church united in the gospel. I still have more questions than answers, but let me offer the following seven suggestions to fellow pastors. My prayer is that these encouragements would help us all shepherd God’s flock more faithfully in light of the diversity of his sheep.

1. Remind your people that they are new people.

Fundamental to our new life in Christ is the acquisition of a thoroughly new identity. No longer are we defined in an ultimate sense by our social status, skin colour, nationality, marital status, or anything else. Rather, believers are now defined by God’s love for us through faith in Jesus Christ. We have been saved into a family, a people, a race (1 Pet 2:9-10), and those relationships define our identity in Christ.

Further, it is the local church where this new familial identity is lived out, where our new identity as brothers and sisters is displayed. Pastors should therefore help their people view themselves as redefined by their relationships with the other members of their local church.

2. Use one language in your church.

During my seminary days I was part of a church that aimed to reach Francophone refugees from Africa. To this end, the church hired a pastor from Ivory Coast, and to some extent the ministry to these people was quite fruitful. But when we tried to host combined services in a display of being one church, the cracks began to show. As much as we observed our people trying to love and understand the culture of our French-speaking brothers and sisters, the language barrier was real.

There is at least one barrier that won’t be overcome until the last Day: language. Until that Day, it is best to plant separate churches for different language groups. Furthermore, in the cases where there are multiple languages spoken among the members of one church, it’s neither wise nor biblical to have people preach, read, sing, or pray in a language that is not shared by every member (1 Cor 14:16-17). Life comes through the Word, and so people must be able to understand the words in order to find life.

3. Don’t feel you must look like the sheep.

In recent years, more and more non-white people have moved into,what were white neighbourhoods during apartheid. In reaction to this, I have heard some well-meaning white Christians suggest that a black pastor needs to be placed in churches in those areas so as to better serve incoming non-white families. I have heard black Christians say they feel better when a black person is upfront, preaching or leading.

I don’t want to downplay the real cultural differences among various ethnicities. Nevertheless, this line of reasoning wrongly views ethnicity as an insurmountable relational barrier. (see Eph 2:16ff). Indeed, such reasoning is contrary to the way Jesus thought about crossing the ethnic divide: the man he choose to take the gospel to the Gentiles was not himself a Gentile, but “a Hebrew of Hebrews.” While it may be easier to befriend someone who shares my culture, what is most needed in gospel-ministry are under-shepherds who truly love the Chief Shepherd and who are utterly committed to serving his sheep (Jn 21:15ff).

4. Help the oppressed to turn from hate.

“I think you are being racist.” That is what my wife said to me when we were still dating. She was referring to my attitude when grading the work of black students in my university tutorials. And she was right! I admit that when I saw a black (Zulu or Xhosa) name on the paper, I immediately thought, “This is probably not going to be very good.” My own racist heart shocked me, especially since I despised Apartheid. Interestingly, when I recently shared my past racist behavior with black Christian friends, they were able to reflect on their own racist tendencies toward white people.

Here’s the point: racism, which is really just one form of human hatred and sinful favoritism, is not the sin only of one ethnicity. Favoritism and hatred comes rather easily to all of us, even when we have been on the receiving end of racism. Church unity requires the loving, humble efforts of all involved. And unity is hindered if some sheep see themselves as incapable of racism. Shepherding those who have been victims of racism means, in part, helping them guard their own hearts from responding to evil with evil (1 Pet 3:8-12).

5. Ask yourself the hard (racist) questions.

Not everyone is a racist. Many I hope are not. Nonetheless, I think its wise for every pastor to ask himself the hard question, “Do I have a racist heart?”2

First, it is not uncommon to harbor racist attitudes without being aware of them. And to the extent that the broader culture is racist, as was the case during Apartheid, it’s very difficult not to be negatively influenced.3

Second, if you discover some racist tendencies in your heart, and if you diligently to turn to Christ for help, this experience affords you the opportunity to speak personally of the redeeming power of the gospel for your racism. It is always helpful for Christians to hear testimonies of the gospel’s work in others’ lives, including its work against the sin of racism.

6. Be careful of importing the world’s vocabulary.

The unbelieving world around us struggles to address the pain and evil of racism in a way that is constructive and useful. Current politics in South Africa are too often characterized by emotive rhetoric that does little to foster attitudes of forgiveness and nation-building. For this reason, pastors need to be careful about importing terms like “white guilt” and “white privilege” without carefully scrutinizing such vocabulary in light of Bible. It’s easy for the unbelieving mindset and heart attitudes attached to these terms to be imported into the dialogue of the church. And this in turn may allow sinful attitudes like hate, unforgiveness, and pride to sneak into the discussions, sometimes even driving them.

Pastors therefore ought to help their people think about racism in light of the Bible, particularly in the terms of sin, God’s sovereignty over evil, forgiveness, and Christian stewardship.

7. Preach gospel-comfort from the Judgment Day.

All evil cannot and will not be dealt with sufficiently by human courts or councils. Full and lasting justice will only come on the last Day, including the justice for the many atrocities committed by racist groups and individuals.

Therefore, those who have been hurt by racism need to be reminded to look beyond this world for justice. They should hear that God sees our hurt and will one day give back to those who injure his people (2 Thes 1:5-7). This should help those who suffer to not become angry and embittered, but to pray for God’s mercy even over those who hate us (Matt 5:44-45). After all, it is Jesus Christ alone who saves us from the coming Judgment, not our works of (racist-free) righteousness.

*****

1 The Coloured people comprise the ethnic group of people who originated in the Cape, whose ancestry is diverse, including Khoisan, Xhosa, European Settlers, and slaves imported from the Dutch East Indies. Coloured people are considered a distinct ethnic group from black groups in Southern Africa, e.g. Zulu people.

2 I trust it’s clear that exploring this question means asking more specific questions, e.g. “Would I welcome a son-in-law (or daughter-in-law) from another ethnicity?” It also probably means having this conversation with someone who knows you well, and will speak honestly to you.

3 One example of this is found in the Coloured community in South Africa. For many years coloured parents were more pleased to have babies who were fairer-skinned and whose hair was ‘straighter,’ i.e. babies who looked more ‘white.’ Clearly this preference was instilled by the broader racist culture.